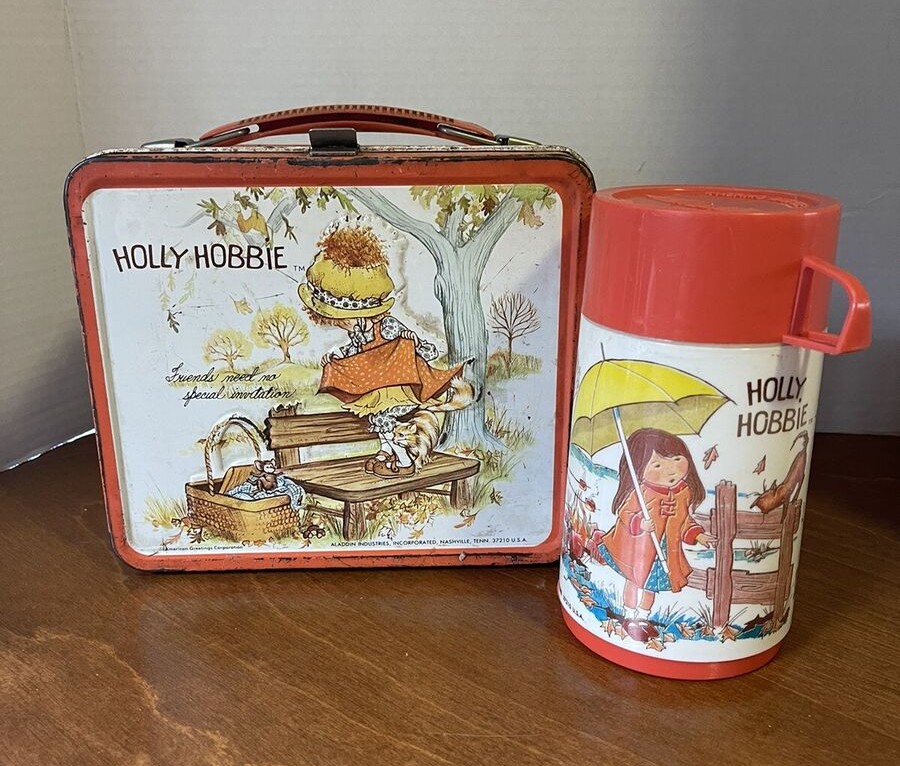

Lunchtime was a big deal during my elementary school years. I recall spending much energy on exactly which lunchbox would provide my “ethos” for the upcoming year. After all, during every lunchtime, that lunchbox sat in front of me, open, back side available for all to see. Everyone at those long cafeteria tables would set up their boxes, pull out the thematically matched thermos and unscrew the cup and lid, take out the various foodstuffs, and spread it all out on the opened lid.

Yes. The lunchbox was ME. Who was I each year? Was I Holly Hobby? Peanuts? The simple butterfly design with flowers? Fairies?

The drama of the annual lunchbox choice still resides in my psyche.

So when I read Anne Lamott’s book Bird by Bird and her chapter about school lunches, I immediately resonated. As she describes, there’s so much going on when I consider my school lunches back in the mid-1960s. If I would try to write the scene, I might find myself overwhelmed. The lunchboxes, the long tables, the smell from the hot food line on pizza or taco day, the small square milk cartons, the cliques, the snack trading, the teachers walking around and monitoring, the noise and clatter before recess, the internal angst of walking across the cafeteria in a new outfit …

So much. Too much.

Lamott addresses this, giving advice to writers to not try to capture it all. Instead, to write the “one-inch picture frame.” To take a mental shot of the entire cafeteria scene, and then to Zoom in on one small piece of it — such as a lunchbox.

On her Instagram page beside a photo of a small picture frame, Lamott writes:

This is the 1” picture frame I keep on my desk to remind me that all I have to do one day at a time is to write the one scene or portrait that I can imagine or remember and see (if I squint) through that one inch picture frame. Not a whole chapter or essay or book, just one piece of that, the best I can do. I’ve had my writing students give these to each other for nearly 40 years now. It seems silly, but it helps a little, and that can be a miracle.

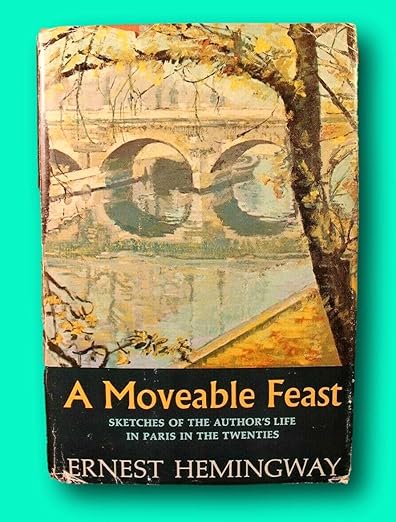

It sounds similar to Ernest Hemingway’s advice, in A Moveable Feast, to “write one true sentence”:

Sometimes when I was started on a new story and I could not get going, I would sit in front of the fire and squeeze the peel of the little oranges into the edge of the flame and watch the sputter of blue that they made. I would stand and look out over the roofs of Paris and think, “Do not worry. You have always written before and you will write now. All you have to do is write one true sentence. Write the truest sentence you know.”

One-inch frame . . . one true sentence.

The idea is to not get overwhelmed. To not give in to imposter syndrome. No matter how many chapters still to go, no matter how long the article, you can just write that one beautiful sentence. You can focus on that one small bit of the big picture, working word by word, sentence by sentence.

Eventually, yes, you’ll go back. You’ll edit. You’ll rearrange. You’ll cut. You’ll write more. But to get there, you need to start.

Break it down. Focus in. Take your time. A little bit every day.

One inch. One sentence.